Breaking the Wall of War and its Impact on Children

Breaking the Wall of War and its Impact on Children

Global Call 2025 Finalist Interview: Social Sciences & Humanities

Myriam Denov is a full Professor at McGill University and holds the Canada Research Chair in Children, Families and Armed Conflict (Tier 1). Her research interests lie in the areas of children and families affected by war, migration and their intergenerational impact. A specialist in participatory and arts-based research, she has worked with war-affected children and families in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Her current research explores the realities and experiences of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. She holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge.

Which wall does your research or project break?

There are 473 million children growing up in war zones, in devastating conditions of violence and deprivation. For over two decades and on three continents, I have sought to make visible the gross human rights violations of children in war and have been a leading and influential voice for ensuring practitioners, governments and the United Nations (UN) better understand, respond to and prevent these violations. I have led multidisciplinary Global South-North teams to holistically tackle the complex challenges of child soldiers, girls in armed groups, children born of war and war-induced migration. I have interrogated the ethics of how scholars engage with marginalised children, implementing innovative, responsible and ethical arts-based and participatory methodologies, radically expanding youth empowerment in research.

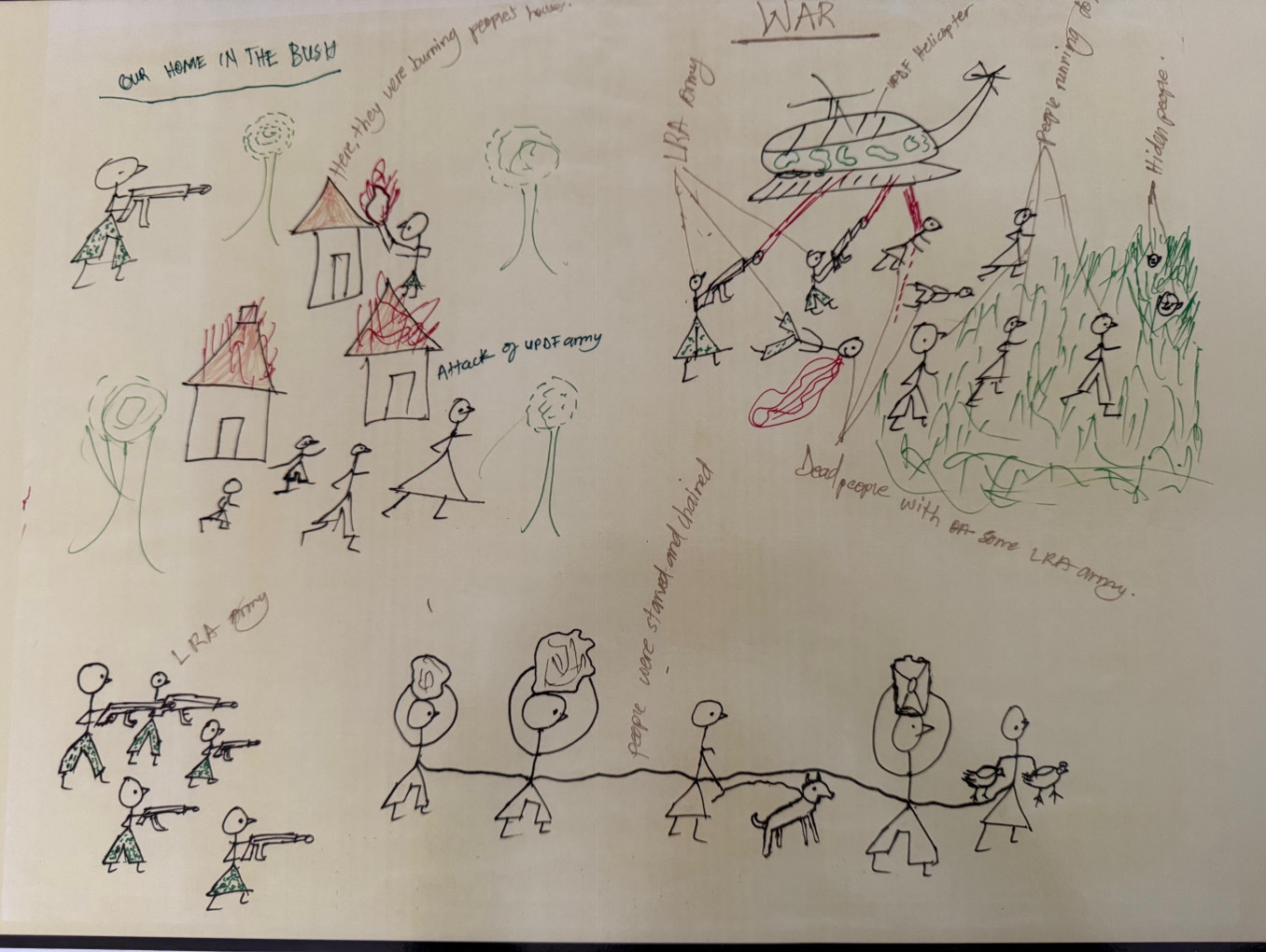

Through my work with war-affected children, I have learned that relying on words and narratives alone often cannot adequately capture or address the complexities and sensitivities of wartime experiences. I have found that arts-based research approaches—photography, drawing, mask-making, theatre and music—offer multiple options for participant expression, as well as provide therapeutic, restorative and empowering qualities and experiences. My research has thus employed arts-based methods that are sensitive to the local culture and are always developed in collaboration with my local research partners. In Uganda, I have used drawing and mask-making to enable children born of war rape to depict their post-conflict realities. In Sierra Leone, photovoice enabled former child soldiers to represent their post-war reintegration experiences. Creative outputs—via exhibitions of photos, masks, drawings and theatre—are key to my dissemination activities, engaging participants, local communities and policymakers who attend the exhibitions.

Through art and participation, my research seeks to break multiple walls:

1) The wall of silence, ensuring the voices, perspectives and experiences of war-affected children are heard and valued;

2) The wall of accountability, where policy, action and change replace global outrage yet inaction; and

3) The wall of passivity, where children and youth affected by war are regarded not as passive victims, but instead active participants.

By training war-affected youth as co-researchers on my teams (these youth engage in data collection, analysis and dissemination), I have sought to transform the way participatory research methods are conducted with youth, promoting ways for war-affected youth to (re)build their own lives.

What is the main goal of your research or project?

Armed conflicts are dramatically altering the lives of children and youth around the world with devastating social, economic, political and psychological effects. My research is concerned with the well-being of children and families affected by armed conflict, with a particular focus on children born of wartime sexual violence. Brutal forms of sexual violence against women and girls pervaded the war in northern Uganda and the genocide in Rwanda. In both countries, females were systematically sexually assaulted on a large scale, resulting in the birth of thousands of children. Born of war, these children are deeply affected by the social upheavals that brought about their conception, alongside their treatment by society on the basis of their biological origins. Research has begun to reveal that these children may face stigma, abandonment, violence, barriers to legal citizenship and be prevented from accessing formal health, education and employment systems. Yet post-conflict policies have yet to address this population of children. Also, noticeably absent from the literature are the voices of the children themselves, particularly their perspectives on the mother/father-child relationship, experiences of community belonging and stigmatisation, and their own unique and long-term needs. Concerted, evidence-based action in the form of policy efforts and the development of best practices for post-conflict intervention are vital for the immediate and long-term rights and protection of children born of wartime sexual violence.

Addressing major gaps in scholarship and practice, my research enhances understanding of the lived realities, rights, perspectives and needs of children born of wartime sexual violence from the perspective of the children themselves, as well as their families and communities. As the atrocities and fallout of wartime sexual violence continue unabated, children born of war and their families and communities deserve a voice, an evidence-based policy response and ensuing action. The insights gained from my research have wider social benefits as they can help to identify and generate best-practices for children born of war, their families and communities that can be adapted, modified and applied across conflict zones worldwide. My project—addressing a vexing and urgent global issue—will lead to a complex, multi-layered understanding of children born of war and their social context, providing attention, advocacy and action, for a still largely invisible group of children.

What advice would you give to young scientists or students interested in pursuing a career in research, or to your younger self starting in science?

I would encourage emerging researchers to take risks with their ideas and to have the confidence to pursue projects and methods that might not be immediately supported. When I was considering bringing young people on my team as co-researchers, some colleagues suggested that I not include this information on my funding proposals, fearing that I might not get funded if it were mentioned. Others questioned what youth could contribute to a research team. As an emerging researcher, it was difficult to make the decision to pursue approaches that weren’t always supported. At the time, I looked to the children and youth themselves to determine if I was on the right track. The children and youth were highly motivated, capable, engaged and provided incredibly positive feedback. Their commitment and desire to continue working together was the proof I needed to keep going. I would encourage emerging researchers to take those kinds of risks as they can lead to important innovations.