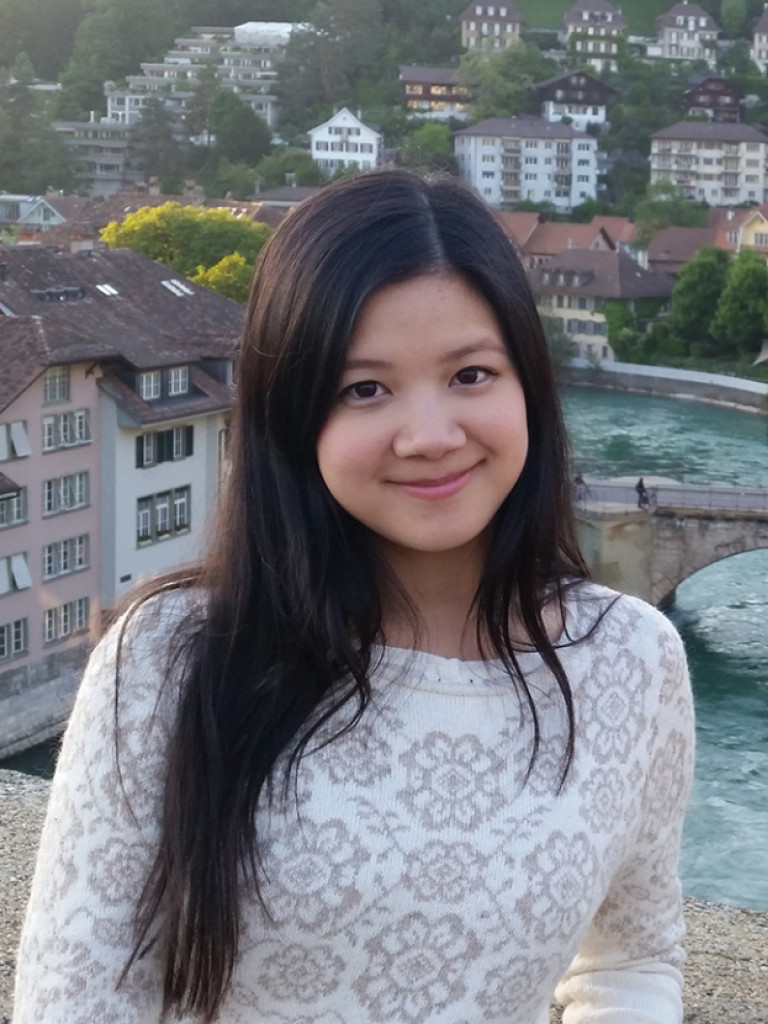

Crystal Chow

- 2019

- Press Fellow

Crystal Chow is an award-winning Hong Kong freelance journalist and feature writer with nearly eight years of experience in covering Southeast Asian affairs, global environmental and development issues for various Chinese-language media outlets. Recipient of a Human Rights Press Award in 2017 and the Environmental Story Merit Award at the Asian Environmental Journalism Awards in 2019, her notable works include the indigenous movement against the then-proposed Baram Dam project in Malaysian Borneo, Duterte’s rise and the “drug war” in the Philippines, as well as the illicit trade of South African abalone and its connections with Chinese markets. Her recent project, supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation, explores the relations between climate-induced displacement and human trafficking in the Central Philippines and the gender-sensitive approaches for community disaster response. She holds an MSc in Global Energy and Climate Policy from SOAS, University of London, with an elective in International Environmental Law. 1. Why did you choose to become a science journalist? I am not a science journalist, but I always have great admiration for what scientists do, and I love to think that at the heart of all scientific endeavours lies the same guiding principle of journalism: the disinterested pursuit of truth - be it about our universe or the human condition. Throughout my career, I have covered various aspects of science, particularly climate change, clean technology, and the marine environment. Dedicated to better informing the Chinese-speaking readers of the multifaceted human impacts of climate change, I am interested in learning about the technological solutions to our world’s environmental crises, and have recently started to explore the ways climate change would affect our food production, land use, public health, and migration patterns. 2. What role do science and science communication play in your country? Generally speaking, science journalism - or the emerging specialism of “solutions journalism” - is less established in the Chinese-speaking region, although there are a few exceptional media outlets that regularly report on scientific discoveries (and occasionally debunk myths and disinformation), such as Taiwan-based PanSci, The News Lens, Hong Kong-based The Stand News, and China-based Guokr.com. Despite the alarming scientific consensus, the climate crisis still hasn’t met with appropriate actions across the globe. One of the main reasons, I believe, is that our media coverage on climate change is overwhelmingly dominated by the fatalistic “doomsday” narrative and the appeal to “feel-good” consumers. While this sort of moralizing rhetoric may sometimes be an effective call to individual virtue, it contributes little to the very discussion we urgently need - the structural changes and innovative solutions critical to our sustainable future, as well as the just, equitable way to hold those who are most responsible for climate change accountable for their failures and complicit inaction. Effective communication of the science behind climate change is therefore particularly crucial in bridging such “knowledge gap” and driving perceptual, behavioural, social and policy changes. 3. What are the main challenges of science journalism in your country? The lack of specialized reporters in science journalism in our region can be primarily attributed to the fact that most traditional newsrooms simply do not have adequate resources to invest in in-depth, critical science reporting. In the relentless news cycle, junior reporters often have to cover multiple issues on a daily basis, making it harder for them to develop the skills and rigour needed to discern false claims from credible sources of information. Their overreliance on external opinions (expert or not) and second-hand information also makes their coverage more susceptible to the exponential growth of fake news on social media. At the same time, there has been a lack of scientists within the research community who are willing to proactively communicate their insights and knowledge with journalists and everyday audiences alike. Hopefully, times are changing: the anti-vaccination movement has, for instance, ushered in a growing, vocal group of concerned medical practitioners and science communicators who are dedicated to dispelling the pseudoscience which threatens public health and disease prevention; Meanwhile, the excessive and indiscriminate use of tear gas by the Hong Kong police force in the recent pro-democracy protests has prompted a series of in-depth reporting on its health impacts across various platforms, showcasing the collaborative efforts between local journalists and scientific professionals. 4. Where do you see the big societal transformations in the future? What scientific research/discovery will change our world? When it comes to the science of climate change, I believe large-scale, commercially viable energy storage would be the key to the sustainable growth of renewable energy technologies. While I understand the notion of offering a technological quick-fix for the global climate crisis has been met with considerable skepticism (justifiably so), I see no reason to oppose to further research on the feasibility of different types of geoengineering solutions. Context-specific innovative approaches to climate adaptation are equally crucial in achieving climate justice - from smart agriculture technology to environmentally-sound alternative air-conditioning in the global south. We also need to learn more about how climate change is going to affect our health, access to resources, migration patterns in different projected scenarios, and how we can withstand and address these impacts in the long run. 5. What book, movie or song has radically changed your perspective? And why? Anthropologist and adventurer Wade Davis’s The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World has instilled in me a love of travel and the appreciation for the diversity of our world’s cultures. British writer China Miéville’s mind-blowing sci-fi novel Embassytown, which brilliantly blends far-future fantasy, mystery thriller, and political allegory to explore semiotic and postcolonial ideas, has left me captivated for days with lingering thoughts on the grounds of our civilizations. Again to name just a few: The 1997 film sci-fi classic Gattaca brought me to the world of great science fiction and gave me - a 12-year-old child at the time - the first glimpse of the many fascinating mysteries of the cosmos and the origin of life. It has also shaped the way I look at human endeavours against the odds, for we are both utterly insignificant and unique in the vastness of space and the immensity of time. Nearly two decades later, I watched the Chilean documentary masterpiece Nostalgia for the Light and found myself profoundly moved. These are two narratively, thematically, and stylistically altogether different films, and yet they evoke a strangely familiar emotional resonance in their insistence on humanity in the face of hardship and injustice.